LSU Innovation Powers the Nation’s Most Trusted Hurricane Storm Surge Forecasting Tool

August 13, 2025

The greatest threat to life during a hurricane often comes in the form of storm surge, ocean water pushed onto shore by powerful winds that can substantially increase water levels in a matter of minutes.

Carola Kaiser

Having a reliable way to know in advance when and where to expect storm surge and the resulting flooding can be key to protecting both life and property.

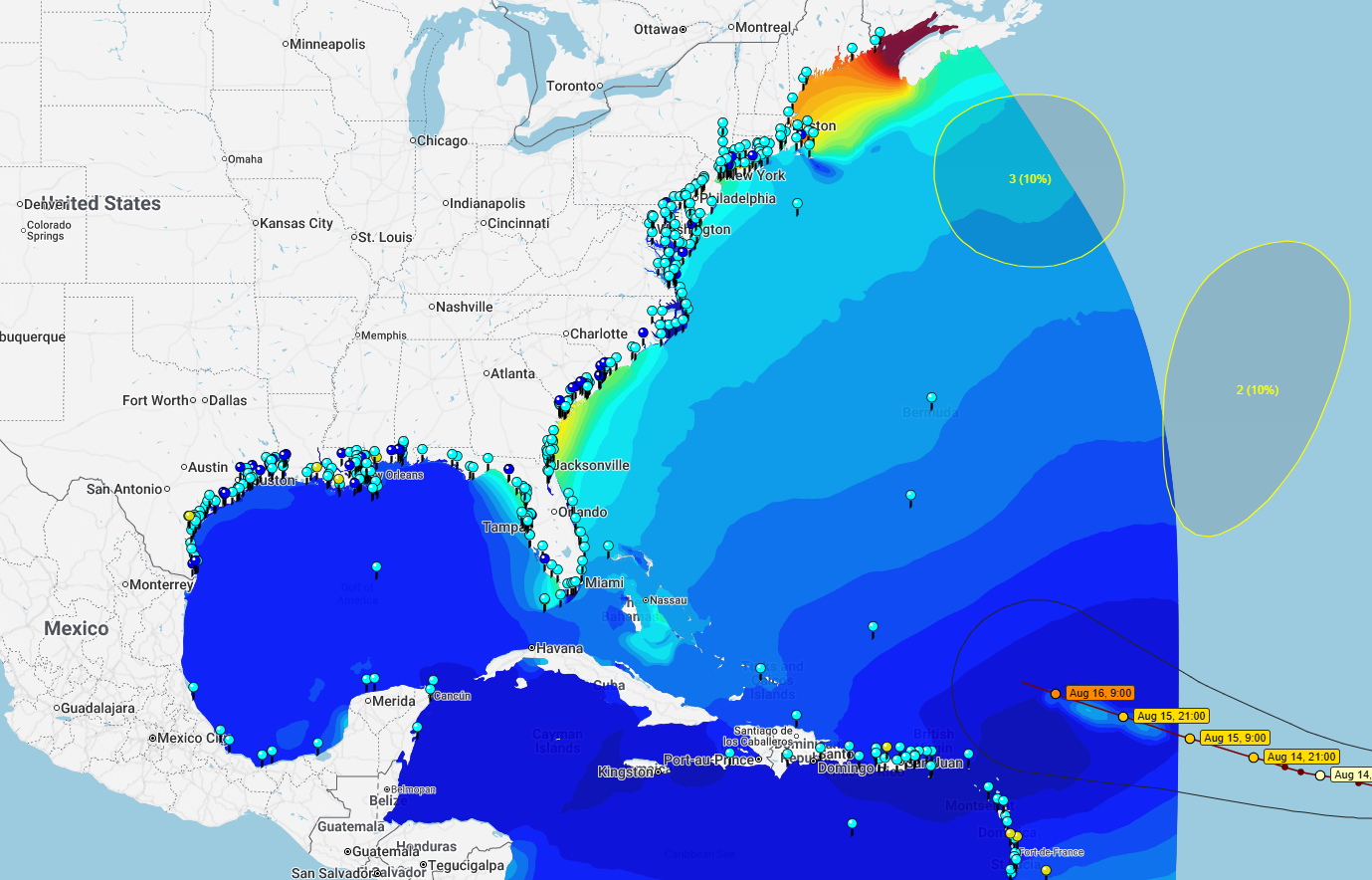

Since its inception in 2006, LSU’s Coastal Emergency Risks Assessment tool, or CERA, has been delivering ever-improving storm-surge forecasts via an easy-to-use website meant for coastal residents and the emergency managers tasked with keeping them safe.

“CERA is an interactive website that helps people better understand the impacts of approaching hurricanes,” said Carola Kaiser, CERA team leader at the LSU Center for Computation & Technology.

Since 2006, LSU’s Coastal Emergency Risks Assessment tool has been delivering ever-improving storm-surge forecasts via an easy-to-use website.

It works by automatically pulling in data from sophisticated forecasting tools and presenting them in an easy-to-understand format. The color-coded water height projections give residents a clear understanding of the potential flooding in their area, allowing them time to make their own decisions on taking precautions, she said.

A more robust version available to emergency management agencies provides proven data to inform timely decisions such as ordering evacuations or determining which floodgates to open or close and the optimal time to do so.

The data is also used by members of the science community as an after-the-fact accuracy test for forecasting simulations.

A Valuable Tool for Public Safety

Hartmut Kaiser

The CERA system is used by about 2,000 to 2,500 emergency management agencies across the country, said Hartmut Kaiser, a lead researcher on the CERA project and a professor in the LSU Division of Computer Science & Engineering.

“They are very interested in using that data because over time it has gained some reputation of being correct, of being reliable,” he said. “You don't have to teach your agents or your offices in the agency how to use that system, because it's Google Maps-based. Everybody knows how to use that, and that's one of the advantages.”

LSU alumni Gregory Grandy is a coastal resources administrator with the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, or CPRA, which was formed in 2005 in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

CPRA, in cooperation with local and federal partners, is tasked with planning, building, and providing technical assistance concerning levees, flood gates, and other protection systems across coastal Louisiana. But when a storm enters the Gulf of America, the focus shifts to supporting storm response, and that’s when CERA proves valuable.

"You have to understand when a storm's coming in, your heart starts to pump a little bit faster. And you need to be right in the decisions that you're making,” Grandy said. “And CERA and the models that underpin it continue every year to get a little bit better and clearly communicate that information so that people who are making those decisions understand when it's time to close or leave a gate open.”

Grandy said having access to CERA and the LSU team during tropical storm threats greatly improves CPRA’s ability to help protect people and property in Louisiana.

“It's an invaluable tool,” he said, “and everybody across coastal Louisiana who operates structures, everybody wants to see the results of the CERA model to help inform their operations.”

Gregory Grandy, left, a coastal resources administrator with the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, meets with engineers Adrian Beltran, center, and Jeremy Fall.

An Introduction to Hurricanes

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina produced a storm surge up to 28 feet above normal tide levels, contributing to billions of dollars in damage in the New Orleans area and along the Mississippi coast.

Carola and Hartmut Kaiser, who had recently moved from Europe to Baton Rouge for positions at LSU, found themselves experiencing the power of nature in a way they had not seen before.

“We came here, we closed on our house, and three weeks later, Hurricane Katrina hit,” Hartmut Kaiser said. “And we thought, ‘Oh wow, that is not what we signed up for.’”

But amid the fear and confusion came an idea: a way to channel Carola’s expertise in cartography and Hartmut’s technical computer skills to benefit their new home of Louisiana.

“So, it was … in some sense life-changing, because it was completely unexpected. And we thought, ‘What can we do? How can we improve the information flow?’” Hartmut Kaiser said.

Carola and Hartmut Kaiser knew LSU researchers were doing hurricane simulations, as well as storm-surge forecasting, and thought they could help visualize that data on maps.

“And with that, it was a great opportunity, which now led to this CERA system,” Carola Kaiser said.

They started experimenting with data produced at LSU in the aftermath of Katrina. Google Maps was a new product on the market and an ideal tool for what they had in mind.

“We generated that image … from the simulation, onto Google Maps,” Hartmut said. They were pleased with the result. “You can zoom in. You can look at things in more detail than if you just look at some generated image. And that's where things started.”

It Took a Team to Build CERA

From that starting point, CERA has grown into a vital tool during the threat of tropical weather, the result of years of extraordinary effort and support by numerous people and groups, including LSU leadership, funding agencies, and the scientific community that develops and continues to improve the forecasting and other tools needed to make CERA run.

“It's definitely a large team effort, and we wouldn't be able to do it without everybody helping with that.”

Carola Kaiser

“It's definitely a large team effort, and we wouldn't be able to do it without everybody helping with that,” Carola Kaiser said.

One important simulation tool that fuels CERA is the Advanced Circulation (ADCIRC) storm surge model, a collaborative effort involving academic, governmental, and corporate partners.

ADCIRC is managed by Clinton Dawson, Aerospace Engineering & Engineering Mechanics Department chair at the University of Texas at Austin, at the Texas Advanced Computing Center, or TACC. One of the nation’s most powerful computing centers, TACC has the capacity needed to support the complicated ADCIRC model, enabling it to perform key functions quickly and accurately.

“The faster people can get the information, the faster they can act on the information. Of course, the information needs to be accurate,” Dawson said.

Following the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2006, the initial process of running storm surge forecast scenarios manually was automated in a project led by Jason Fleming, head of Seahorse Coastal Consulting and managing the ADCIRC Surge Guidance System that CERA closely collaborates with. This team effort enables CERA to deliver reliable and fast real-time storm surge results using powerful supercomputers in Louisiana and Texas and in-house resources at CCT.

In addition to top researchers at LSU and beyond, Carola Kaiser said LSU students have made major contributions to CERA over the years.

“The students, I always say, are amazing because they are fully motivated. They are young and fresh. No mountain too high, no valley too low,” she said. “We always like to work with students. And it is amazing to see how you can influence their career.”

Robert Twilley, LSU’s vice president of research, says CERA exemplifies two main characteristics that he wants the university’s research program to be known for.

“Number one is we want excellence. Excellence comes by performing and being a differentiator in our ability to build things like CERA that no one else can do,” he said. “I also want our research to be known for relevance. And I think CERA has given us both. It is our differentiator both in excellence and in relevance.”

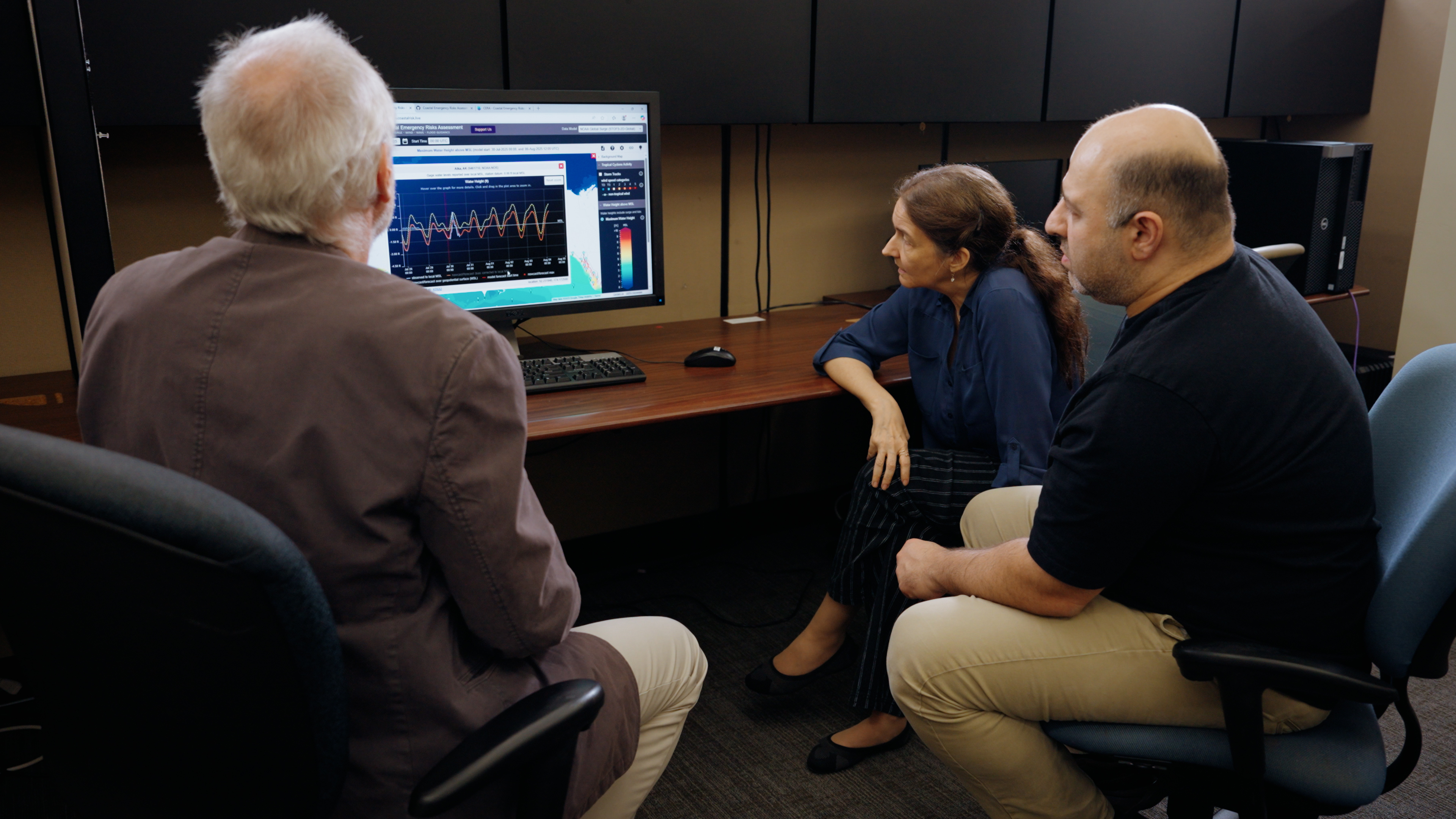

Carola and Hartmut Kaiser review CERA data with Alireza Kheirkhahan, a system administrator at CCT who oversees the CERA hardware and real-time resources.

The Drive to Improve CERA

Carola Kaiser said the team works to ensure CERA is always ready to run at peak performance.

“To be honest, around the year, we do nothing else but testing, implementing new features, conducting real-time exercises to be ready for this one particular storm that we get over the summer,” she said. “It must be a well-oiled engine, as we always say, because storms do not allow any errors.”

One area with great promise for the future of CERA is artificial intelligence.

Noujoud Nader, a research scientist at the CCT, is using AI to help bring more speed, adaptability, and enhanced precision to the CERA system, in part by accounting for biases and uncertainties that are inherent in even incredibly accurate physics-based models like ADCIRC.

“This added intelligence allows CERA to deliver timely, location-specific forecasts that are crucial for public safety,” she said.

“In the next few years, I see AI playing an even greater role in real-time forecasting. Ultimately, I think people can expect forecasts that are not just more accurate, but more actionable—designed around the real questions people ask during a storm: How bad will it be here? When should I leave? What can I expect afterward?”

LSU Innovation to Protect Our State

With Louisiana on the front lines of climate risk, the CERA researchers said having this research conducted in the state is vital.

“It’s not just about advancing technology. It’s about helping families, local leaders, and first responders make better decisions when time and clarity are in short supply.”

Noujoud Nader, research scientist at the LSU Center for Computation & Technology

“The research community around hurricanes is very strong in Louisiana,” Hartmut Kaiser said. “There is a close connection between the local agencies and the research community at LSU, related to tropical storm events.”

He pointed to direct support from the government projects that finance this kind of research at LSU and CCT, an interdisciplinary research center that manages large computing resources needed to handle robust simulations.

“It’s not just about advancing technology,” Nader said. “It’s about helping families, local leaders, and first responders make better decisions when time and clarity are in short supply. I feel a deep responsibility to use my expertise in AI to protect people and make forecasting systems smarter, faster, and more equitable.”

There’s also an element of defending and protecting your home that fuels the effort.

“It's our home. You get directly affected,” Carola Kaiser said. “You go through those storms, you get opinions not only from people that you do not know, but also from your neighbors, from your friends, from your family. And that affects us all a lot.”

Real Solutions for Real Problems

As a public-facing tool, CERA is a valuable resource to everyone from national agencies to individual homeowners. LSU has received account requests directly from the Situation Room at the White House, where top federal officials gather to monitor and deal with crises.

Hartmut Kaiser said the U.S. Coast Guard has reported it has used CERA to decide when and where to move their ships prior to the arrival of storms. “They sent us emails thanking us for providing that information to them, because that allowed them to protect their ships from the storm.”

But one story in particular has resonated with Carola Kaiser.

A CERA collaborator was sitting in a café in Europe with the CERA site open on his laptop, she said, when a woman approached to ask about it. Upon learning the man’s role in CERA, she revealed that she and her parents used the program to decide to evacuate during a storm crisis in Florida.

“We evacuated our parents, and exactly as you predicted, the flooding came in the next day,” the woman said.

“And those are the nice stories that you hear,” Carola Kaiser said. “We do not know how many people look at it or use it in different ways. But the impact is there, and that is very satisfying to be able to help people in such a way.”

Explore LSU’s role in response, recovery, resilience, and research following Hurricane

Katrina.Turning Tragedy into Impact